Home Lyrics Musicians Albums History Interviews Links

|

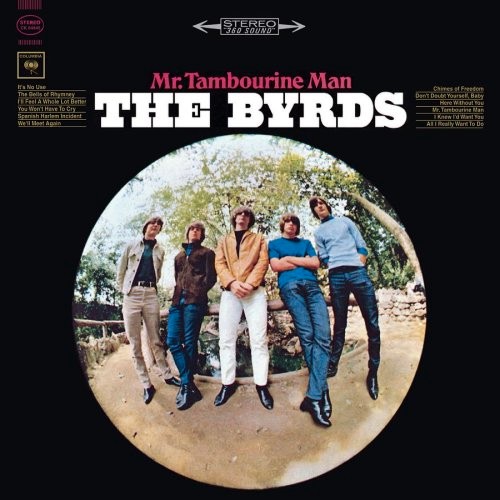

The Byrds speak on Mr. Tambourine Man

also see Hillman speaking on |

|

David Crosby - Byrdwatcher 1998 He (Jim Dickson) was a big influence early, you know, the first year or so of the band. He brought Dylan to us. It's not that we didn't know, you know -- I'd watch Dylan play when I was a kid working in the Village, and he was singing over at Gerde's. And I thought he was a great writer then. Didn't like his voice all that much, but I thought he was an unbelievable songwriter. But I didn't really get him until Roger translated him for me. When Roger took "Tambourine Man" and changed the time and the feel... Roger's a genius, man. Face it, the guy is. He's one of the great storytellers of music ever, and one of the great arrangers. He did the best translations of Dylan's work that'll ever happen, or at least have ever happened, and he made Dylan come alive for me. All of a sudden I realized what the real potential of those songs because I wasn't listening to Dylan's voice, which I found sort of irritating. I think Roger's just an immense talent. David Crosby - Goldmine 1995 There was a guy named Jim Dickson who I met in that same coffeehouse. He heard me singing, and he knew that I didn't know doodly-squat, but I had this pure little voice. He liked the business, and knew a hell of a lot more about it than we did. When I started singing it the Front Room at the Troubador with McGuinn and Gene Clark, I said, "I have a friend who knows a lot about the business. We ought to go sing for him and see what he says." So Jim became our mentor, and then our manager. He brought us a demo of Dylan and Ramblin' Jack singing "Tambourine Man," which was truly awful - two guys that were not too sharp on staying on tune - but it was a great song. Jim convinced us to do it. Once we realized that you could take Dylan and transmute it the way Roger did, we did a lot of them. I'm pretty sure that was the first time anybody had put really good poetry on AM radio. "To dance beneath the diamond sky, with one hand waving free." That wasn't on the radio until then. Chris Hillman - Richie Unterberger ca. 2000 He (Jim Dickson) gave us a great sense of putting a little depth in what we were doing, a little thought. Doing something substantial, and taking -- nobody was really keen on "Tambourine Man" as I recall when we first heard it, maybe McGuinn, but I don't know if anybody else was. But Dickson pounded it into our head, literally, to go for a little more depth in the lyric, and really craft the song, and make something you can be proud of ten to fifteen years down the road. He was absolutely right. When we didn't listen to him, we cut a couple of stupid things on the records. He was a very gifted guy in that sense, and hung in there with us from the get-go. We were all starving, and he sort of guided us, as all young acts need, is that Svengali (laughs). That was Dickson was. He was good at the time. It got a little personal, as things do, and things didn't always roll as smoothly as they should. And we didn'tlisten to him. We had an opportunity to do one of the very first videos, in a sense of 16 millimeter stuff, around Gene's song "She Don't Care About Time." And we were going to send it to England. And of course, it didn't happen, because we got in a big argument with Jim. I don't say we, but David did. And the whole thing was scrapped. And this was '66, or late '65, '66, and we're ready to do this film. Which was really basically the genesis of a video around Gene's song. Of us on the beach, doing this filming. Barry Feinstein was shooting it. Those kind of things, Jim was really good at. We just didn't listen to him. We were wise-guy little punk kids, and he was our big brother-slash-father figure. But he had a tremendous influence on the Byrds, and he pushed for "Tambourine Man," and put himself out on the line for that one. And he was right. And it does stand up 37 years later. It stands up. You hear it on the radio, it's a good piece of music. And regardless of if there's session players on that song, or if we'd have cut it. It's a great song. And at the time, we weren't ready to cut that song. It's almost too slick. Sometimes I wonder, would it have been interesting for us to have cut a version. It might have taken away a bit of that slick pop sound, but it's okay. And I love it to this day when somebody says, yeah, you guys didn't play on the first album. (laughs heartily) You gotta put it on, you know it's us, because it's all kinds of weird stuff going on. That's not session players on the first album. But you know it is on "Tambourine Man" and on the flipside, "I Knew I'd Want You." It was the right thing at the time. And in those days, we got a singles deal. You know, "if you guys do good with a single, we'll see if we can let you do an album." And I think, in hindsight, those were the right moves to make. Roger was the guy. And as I said earlier, Roger had more time on the battlefield as a backup player. And he had good time. And he could be out there with session guys and do it. We weren't disciplined enough in that area. Although I had done lots of sessions on mandolin. But bass, it was another animal. It was a brand-new deal. For me to be next to Hal Blaine on that song, yeah, I probably could have pulled it off. But not as well as Larry Knechtel. Larry played with a pick on that song, and Joe Osborne was another session guy that was around L.A. He played with a pick. And McCartney played with a pick. I played with a pick. That's the way I learned. And it's only in the last couple of years I sort of goof around with my fingers on the bass. Anyway, back to Dickson -- Dickson gets a lot of credit for this whole deal. He set this thing on track. And we derailed it ourselves. That's all I can tell you. As things work out, it was time for maybe us to part company with Jim. But it wasn't long after, we lost a bit of our direction. And you can trace that to about nine million other bands, too. While I've been writing this book, I still get people saying to me, the Byrds didn't even play on their own records. But there's absolutely no evidence that sessionmen took the place of the Byrds, with the exception of those two tracks on the first Columbia single. Even on the first album, everything but those two songs is the band playing. I guarantee you, you just tell anybody that says it, listen to the record [Mr. Tambourine Man, the Byrds' first album]. If those are session players, then we must have had the C-level group of 'em. 'Cause it is us, and you can tell how we're playing. It doesn't stand up to the "Tambourine Man" track, as far as that preciseness. And it's okay. Because I tend to like the raw edge of the band, as opposed to the slickness of the session date. But hey, whatever, people say all kinds of stuff. It's funny, though. We went from being better live in the early days to better in the studio later on, and switched. And we became too lackadaisical on stage. We were a better studio band as the years went by. We made some good records, we made some silly ones. But everybody else does, too. I think Dean (Webb of The Dillards) helped David work out his part, the tenor part. Basically, "Tambourine Man" -- I didn't sing on that, obviously, but Gene and Roger doubled the lead and got this really nice sound, because the two voices sort of meshed real good. I think Dean probably worked with Crosby on that, giving him some ideas. Because Jim Dickson, the fellow that we worked with in the studio, had done lots of projects with the Dillards and Dean, I'm sure that it happened. I don't recall it, I don't remember if I was even there at the time. Chris Hillman - George Bennett 2006 It always strikes me as funny when I've read in the past that the Byrds didn't play on the first album. All anybody has to do is compare the recording of 'Mr. Tambourine Man' with the album cuts. I still think the original single, ('Tambourine Man') was way too "slick" but I understand Columbia's reluctance to not use us as we were raw back then but still the Band would have probably delivered a more "soulful" rendition. Chris Hillman - Portfolio Weekly 2006 A lot of bands in those days, with the exception of The Beatles, didn't play on their own records. But -Tambourine Man- was the only song the band didn't play on. Columbia Records was sort of hedging their bets, 'we're giving these guys a singles deal;' meaning that if the single takes off, we have the option to do an album. We played on everything else; in fact I will go on record saying we were better in the studio than we were on stage. We took sort of a lackadaisical attitude onstage but in the studio we made pretty darn good records. We wanted to be like The Beatles until Jim Dickson steered us away from that and pounded it into our heads to go for substance over style, go for depth in the material. Here's a song-Bob Dylan, 'Mr. Tambourine Man,' it hasn't been put on a record, Bob just wrote it-listen to this. And everybody was a little wary of it. But McGuinn, with all due respect, put that arrangement to it. So our manager steered us out of emulating The Beatles and trying to be some sort of second rate American Beatle band with clothing, hair and all of the accoutrements, and put us more into our own thing. It took a while, but once we started to get clear of the Bob Dylan covers, we started to develop our own style of music. We got songs like 'Eight Miles High,' but the best known of our songs is probably 'Turn Turn Turn' which is out of the Old Testament, written by King Solomon with music by Pete Seeger. Roger McGuinn - Folk To Flyte 1996 Jim Dickson had become our manager. He realized the importance of getting us a radio hit with our first single. The Columbia deal was for one single record only. If we didn't get a hit, we were back on the street! Jim had overheard some record producers talking about a Dylan song that Dylan wasn't able to use because someone was singing out of tune on the track. So Dickson wrote to Dylan's publisher in New York and had them send a demo of "Mr. Tambourine Man" to California. We listened to the demo in the studio, and Crosby said, "I don't like it, man! It's got that folkie 2/4 beat and it's too long! Radio is never going to play a song like that!" We listened to the demo in the studio, and Crosby said, "I don't like it, man! It's got that folkie 2-4 beat and it's too long! Radio is never going to play a song like that!" David had a valid point. Folk music had been out of favor in the Top 40 for a while. Only British music was making the charts, and the songs were short - about 2 minutes and 30 seconds. I had an idea of how to save "Mr. Tambourine Man." I'd been playing around with some Bach licks on the 12-string and thought, "What if I put an intro like this . . . and we change it to a Beatle beat?!" It worked! We got a Number One hit and were allowed to record the rest of the album! Our sound wasn't quite formed by the time we recorded the single for Elektra. It was close, but it took Terry Melcher and his knowledge of the studio scene and beach music to give The Byrds the winning edge. Roger McGuinn - mp3.com 1996 The feeling was one of joy and disbelief! We couldn't fathom that we'd created something so overwhelming. Roger McGuinn - musicangle 2004 We needed a hit single. We only had a single deal with Columbia, it wasn't for an album. So, Dickson was hanging out with Paul Rothchild, who was a producer at that point for folk music. He used to scout around and he was talking about some sessions with Dylan he had recorded with Rambling Jack Elliot and they had this song, and they couldn't use it because Jack was out of town. The rumor was that he was really drunk. And Dickson heard about that and he said to Whitmark and Sons, (Dylan's publisher,) and he got the acetate of it, and he brought it to the studio and we were all standing around in front of these speakers and Dickson played it for us. It was in 2/4 time, about 5 minutes long, and Crosby immediately piped up and said, "I don't like it, man! It's that 2/4 beat! It's never gonna play on the radio!" And so I said, yeah, what if we cut it down to one verse and put a Beatle-beat to it, and I came up with a little lick for the front. I didn't mind the level on it so much as the EQ. I think the EQ was a little too treble for my tastes. I don't know if they were going for the original or what, but I don't like it that thin. Melcher didn't believe in stereo. Melcher thought stereo was a gimmick that would fade away -- a passing fad. RM: Actually, when I first heard it, it was in the studio after we did it, and I was blown away. I couldn't believe that we had done that ourselves. Of course, it was a studio band, and that's why the track was so good and powerful, but the vocals were great after we did it, it was so clean it sounded like someone else's record. I was really thrilled with it. I was scared to death (cutting it with eight session players), like a little kid. They were going, "Aw, don't be afraid, it'll be okay." They were really supportive and nice about it and I was really nervous. The next day when we were doing the vocals, the microphone weighed about five pounds, and I had this really heavy feeling in my chest. We got through it okay. (It was a good feeling to hear it on the radio). It was, except that we were broke. It didn't connect. I was walking on Hollywood Boulevard and I heard a car go by with the song playing and I went, "Wait a minute! There's something wrong here!" I didn't have any money, and I'm walking in these dirty jeans and there goes a convertible down the street playing my song. They (the other Byrds) weren't very happy about it (the session players), but I think it was for the best. It wasn't that strong a recording band at first, and we did need a hit. Crosby really yelled and screamed about it. There was never really any intention of using studio players beyond the single, so that was the only time we were going to do that anyway. I loved Terry (Melcher). He had a real feel for the music. He was a little bit of a spoiled Beverly Hills kid, so it rubbed people the wrong way but I could relate to him all right. The politics of the time sort of got Terry moved out, thinking that maybe Dickson would be our producer, but Columbia didn't have that in mind. They assigned us Allan Stanton, who was really just kinda a square, unhip old guy. He was totally out of it. He was like a caretaker -- he would keep me after school, asking me what's wrong with Crosby. That faded away, and Terry Usher was great. He was very imaginative and fun, fun to work with. He actually contributed musically. We were just trying to keep the beat. We were coming from a folk background where the beat wasn't really an important factor. But in rock, the dancers would fall down if you didn't keep the beat. We had to learn how to play in rhythm. That was our main concern, really. Sonny and Cher did more of the Dylan version of it ('All I Really Wanna

Do'), with the 3/4 time -- they kept all the verses. We tried to make it a

4/4 beat, and turned one of the verses into the bridge. I think it kinda

weakened it. In hindsight, we should have kept it the way they did it. Oh

well. Terry (Melcher) chose (the material for the records). It was his decision -- like he turned down "You Showed Me," which became a really big hit. I like it (the Mr. Tambourine' album). I like the period that it

represents. It was young and fresh and starry-eyed and laughing. Chris Hillman - Musicangle 2004 I wasn't smart enough at the time to see exactly how good that song ('Mr. Tambourine Man') was. I was just the bass player, and I went, "Oh, blah blah blah," and all, but it's a wonderful song. Then, it was a great song and it was a great bit of foresight to do that. McGuinn sang it great. You know, it's funny, I listen to the cut of it, which is the one or two we never played on (or the B-side), but I said, "I wonder what it would've sounded like if we had played on it," but it's very slick and Roger adds this real good vocal to this very slick track. The only thing I miss is The Byrds' essence, this really rough edge that we had. 'Here Without You.' There's an interesting song with Mike Clarke. There's Mike Clarke doing something that's very interesting. Yeah (the cymbals). Doo, badadada, doo. It's like a jazz 6/8 waltz type. You know the story of 'All I Really Wanna Do'. We were playing Zero's when we just started to hit, and Sonny and Cher were in the audience, in the front row. I saw them sitting there, I think they were called Caesar and Cleopatra. They were studying us, and then, of course, they came out with "All I Really Wanna Do." They did a pretty good job on it. They did it a little more towards the way Dylan wrote it. Yes, he (Gene Clark) did('You Don't Have To Cry') with McGuinn. When you play the older version, the little extra 12-string licks that McGuinn did on the final version, track 4, really add a lot to the song. It's nice. We all felt great (hearin 'Tambourine Man' on the radio). I think it affected Roger more -- here he was, his guitar and his singing. He was a twenty-one year old kid who did this wonderful vocal, really right from the heart. I think Roger really felt great. I felt good, too. If I played on it or not really didn't matter -- I was in the Byrds. I felt great, but I felt sort of not as connected. David Crosby - Musicangle 2004 DC: We were driving down the street in a black '56 Ford station wagon that we had bought from Odetta for $400 and we heard it on KRLA and they played it ('Tambourine Man') two times in a row and we pulled over to the side and we were like lunatics! We were just stunned. We couldn't believe it. We'd heard that Tom Donahue had played it up in San Francisco but that didn't mean anything because we hadn't heard it and here it was coming out of the radio as we were driving along. It was wonderful. DC: And they wanted to keep on doing it that way (recording with session musicians), which was the standard practice in the industry at that time. That was how you did that. Well how it was was they didn't have anyone else under contract except McGuinn and they said 'okay that's a great single record, now you guys go in and do the album get those same studio musicians' and Dickson said gee, the guys don't want to do that. They said it doesn't matter what they want, go get some other guys. He says, well I can't do that 'cause one of 'em is the guy who sings that harmony. They said, well okay, sign him get rid of the other ones except the ones who'll do what we tell them and I said no, sorry, that doesn't work, it's a band and we're gonna play it ourselves and they said 'noooo' and we said okay fine then you don't get a record and they had this single rocketing up the chart. They said 'you can't do that!' We said we are doing it. Either we play the record or you don't get a record. And so they had to sign everybody and we did all the music. I loved that one ('I'll Feel A Whole Lot Better'). I loved any one where you could hear my guitar. You can definitely hear it there. I liked that lick. All (songs) done very quickly. No study up. We just kind of played them through, learned them and recorded them. David Crosby - CS&N Biography 1984 Dickson was the one that convinced us to sing Dylan songs. He knew him and got a test pressing of Tambourine Man before it was out. We weren't sure about the song, but Jim got us to try it, and it worked. He didn't think we were strong enough on our instruments to cut it. Dylan could have been a real shit to us (when he dropped in for a listen). But he liked us. Maybe he felt an obligation to come by, but we didn't care. We were still starvin' kids and Dylan was, well, Dylan. Columbia wanted us to use studio guys again (for the album Mr. Tambourine Man). But we threatened to quit if they were gonna make us do that. From the start I was mostly into harmony. That's what I dug. That's what I was best at. And most of the time Gene and Roger would be on the melody, so I had all this space, I could shift around between the third and the fifth intervals. I came up with some weird, beautiful shit, man. It was great fun. Roger McGuinn - CD Liner Notes 1996 At the beginning (Mr. Tambourine Man) it's me speaking to God, saying 'Play a song for me'-...it's a spiritual testimonial--I got this overwhelming feeling of electricity with it. Like 'My hands can't feel to grip'. It was such an experience that I couldn't do anything except submit (Subud). After Jim Dickson picked 'Mr. Tambourine Man' we got into Dylan. It was a mutual decision. I'd come up with the guitar part and Chris would come up with the bass part. Dylan was aware of what we were doing and liked the idea. David Crosby - CD Liner Notes 1996 Gene did try to emulate the Beatles and he would try to play folk changes. His songs had good chord structures. You'll notice that they never had just three chords, there were several chords involved, and they were good chord structures with good melody. Gene had a pretty good way of stringing the melody across chords. Chris Hillman - Uncut 2003 We weren't a garage rock band. The uniqueness of the Byrds came from having no idea what to do, except trying to copy the Beatles. We worked this out trial and error every night. We were trying to come up with the sound, which we did eventually. They watched the Beatles and saw where John Lennon sometimes doubled the lead with George Harrison or Paul McCartney. Gene Clark - John Einarson Tambourine Man Book 2005 I was the only one who was really writing a lot in those days. I'd come into the group with a whole album's worth of songs ready and it quickly became clear that I was a lot more comfortable than the others and a lot more prolific at songwriting. I didn't feel slighted that my songs were on the B-sides. Of course, I made a lot of money. The Byrds had so much character: you had McGuinn with the 12-string and the glasses and Crosby with the unique hippie thing - people weren't into that yet. A lot of these things overshadowed a lot of the songwriting and things like that. So maybe, in a way, being in the background kind of created a mystique that, in the end, might even be beneficial. I certainly didn't suffer that much. There was a girlfriend I had known at that time, when we were playing Ciro's. It was a weird time in my life because everything was changing so fast and I knew we were becoming popular. I could fell this thing happening, I didn't know how far it was going to go, but I believed in the 'Tambourine Man' thing and all that. This girl was a funny girl, she was kind of a strange little girl and she started bothering me a lot. And I just wrote this song 'I'm gonna feel a whole lot better when you're gone', and that's all it was, but I wrote the whole song within a few minutes. Roger McGuinn - Barnes & Noble 2006 Terry Melcher would be the star of the show. It was his ear that got "Mr. Tambourine Man" to sound creamy and like a big hit. He had that Beach Boys sensibility; he was friends with Bruce Johnston and some of the Beach Boys. In fact, on the session I was on the only Byrd allowed to play, and the rest were Hal Blaine, Jerry Cole, Larry Knechtel, who later was in Bread.-Terry really made it a hit.

|