| Chris Hillman - Connect Savannah, Jim

Reed, November 2008 So many of my friends have fallen by the

wayside. Two friends in the Byrds have died and Gram. But it was by their

own choice! No one put a gun to their head. I could have been a statistic,

but I never lost my sense of decency.

The Byrds weren't really a rock band. We just plugged the instruments

into the wall and started learning! (laughs) We had no blueprint or preset

idea in our minds at all. I think I can look back at that band today

-which is almost 45 years later- with pretty clearly. You know, The Byrds,

we never got really rich. We did quite well relative to the time, but what

I'm most proud of that far outweighs any monetary gain is that we left a

musical path for everyone to follow. Be it the Eagles, or Bruce

Springsteen or Tom Petty - who has always acknowledged it. I mean, I don't

even know anything about Kenny Chesney, except that he's a huge country

star. But I saw an interview the other day where he was saying that he

felt there wouldn't even be any country music today without The Byrds,

because we had folks like Vern Gosdin -who was an old band-mate and friend

of mine- open up for us. It was a very nice sentiment.

All of my bands have had their defining moments. It's just that the

Byrds were the most well-known of them all. As I like to say, it seems

I'll never get fully out of the nest. (laughs) We had a wonderful man

named Jim Dickson who was our manager. He drilled into our heads to go for

substance more than anything. He told us we should try to make music we

could listen to in 30 or 40 years and be proud of, rather than to go into

the "boys and girls" territory. Of course, since we had such gifted

songwriters as Gene Clark and Roger and -a little later on- myself to an

extent, it worked out well.

Roger McGuinn - Barnes & Noble 2006

The thrill of being No. 1 with the Byrds was great, but it had some

side effects that were not wonderful, like the pressure. It was kind of a

dizzying experience. But this is just wonderful; there's nothing bad about

it. I feel great now in my life.

I have two favorite spots in the Byrds' career. The first was the

excitement of going from zero to 60 in two seconds. We were starving

musicians on the streets of L.A., taking buses around, living from the

charity of (manager) Jim Dickson, who would buy us cheeseburgers once a

day, and that's how we stayed alive, and then we were meeting the Beatles

and having No. 1 hits and hanging out with Dylan, and going to a height

that few people can imagine.

Memories of the Byrds as told to

Camilla McGuinn

In July 2005, I wrote the first

"Roadie Report" for Roger's web page. I wasn't sure I wanted this personal

road diary to come under scrutiny of the world, but several different

prompts set me to writing. After a few BLOG entries, I received an email

from Jim Dickson, the godfather of the BYRDS, asking if I would like to

write about some of his memories. I was honored and curious. Many

different writers have chronicled the story of the Byrds in detail. I

didn't feel I could add much to those details, but sometimes as we travel

the world together, Roger will reflect on a memory I haven't heard.

In May 2006, I

began incorporating Jim Dickson's memories into the BLOG. This summer

hiatus seemed like a fine time to share some more of the stories I have

heard along the way about a magical time in the history of music. I will

not be documenting a detailed description of the BYRDS history, just a few

of the memories of old friends.r>

1963

Bob Hippard, Hoyt

Axton's road manager, almost didn't recognize Jim McGuinn as he walked

toward him from the airline gate. This 21 year old who had toured two

continents, played Carnegie Hall, been on national television, performed

with world renowned musical artists, recorded on hit records now looked

like a vagabond. His hair was long and combed forward, his big black

crumpled raincoat looked huge over his thin frame and his pale skin was a

sharp contrast to the warm southern California sun, but there was a glint

of expectation in his eyes and in his walk.

Jim's finances were at

an ebb, so Bob drove him to Hoyt Axton's house. Bob had arranged for Jim

to stay at the guesthouse, where Hoyt's mother, Mae Axton, resided when

she was in town. They deposited Jim's bags and musical instruments in the

pool enclave. As they walked back to the car to go search for a bite to

eat, Hoyt greeted them in the driveway. This down home Oklahoma boy

grabbed Jim's hand and invited them both into his home for refreshments.

After hours of munching and smoking a vast quantity of imported Indian

hemp, Bob reminded the musicians they both had a show the following night.

The Troubadour Club in West Hollywood was one of folk music's hot

spots in town. Jim had spent many hours on previous sojourns in Hollywood

practicing his craft and meeting other artisans in the front room of the

club, The Folk Den. Hoyt had recorded his album, "The Balladeer," in the

club and was always a welcomed artist.

Jim was going to open the

show, then singer songwriter; Roger Miller would precede Hoyt. Jim was

tired when he sat down on the lone stool on stage. He began to quietly

sing the Scottish folk song "Wild Mountain Thyme" but he became energized

when he incorporated a Beatle beat to the lyrics. He loved it, but the

audience didn't. There was no response when he finished the song. The rest

of the 30 minutes dragged on.

Roger Miller was tuning up in the

small dressing room, when a very dejected Jim walked in and sat down on

the other chair. "Jim, I liked what your doing out there." Roger smiled at

Jim as he shook his head. "I watched you for awhile and I noticed

something." Roger softly spoke. "You got mad at the audience. They notice

when a singer doesn't like them. You might do a lot better if you didn't

show how upset you are when they don't appreciate what you're trying to

do." Roger left the dressing room. Jim could hear the enthusiastic

applause greeting Roger Miller. He knew he needed to take the advice he

had been given and change his attitude.

The next couple of nights

were not any easier for Jim, but his attitude changed. He was ready to

work hard with the hope some lone person would understand where he wanted

to take his music.

One night, someone did. Gene Clark, a newcomer

to town, fresh from the Missouri folk circuit, was in the audience. As

soon as Jim was off stage, Gene went to find him. This soft spoken, good

looking, dark-haired musician was excited about Jim's innovative way of

combining folk songs to the Beatles' beat. Jim's spirits lifted and they

both agreed to meet the next day in the Folk Den to write some songs.

The collaboration between Jim and Gene was electric. Gene's lyrical

genius and Jim's musical knowledge took these two hungry artists to new

heights. Their voices blended beautifully as they sang the new songs they

penned. When Jim began playing one of the new songs, "You Showed Me," he

felt his guitar move with an almost spiritual energy. He knew something

wonderful was happening.

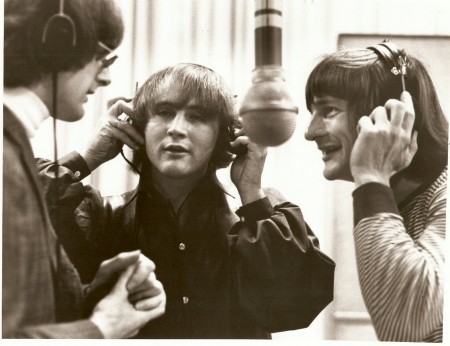

TwTwo days into their song writing

adventure, while they were jamming in the Folk Den, a student actor turned

folk musician, heard them singing. He walked over and added an incredible

harmony. During Jim's first trip to Los Angeles in 1960 to accompany the

Limeliters, he had spent a couple of weeks hanging out with this

actor/singer. As the trio's voices blended with a harmonic brilliance,

their eyes flashed at each other with looks of wonder. Something awesome

was happening. David Crosby hyperly shouted, "We make beautiful music

together!" Jim wasn't sure he wanted to work with this high-energy

songbird. David saw Jim's hesitation and slyly mentioned he had a friend

who would let them use his recording studio for free. Jim's qualms were

quickly surpressed.

Jim Dickson was a producer for World Pacific

Records. One of his productions, "12 String Guitar" sold several hundred

thousand copies, enough to save the label from bankruptcy. World Pacific's

owner, Dick Bock, rewarded Dickson with the key to the studio to use for

his own purposes whenever there were no paying sessions on the schedule.

Dickson went in search of new talent to record demos in the studio.

One night at the Unicorn, L.A.'s first coffeehouse, he heard David Crosby

singing and being ignored by the audience. He was struck by the quality of

David's voice. Dickson's first recordings with David were with studio

musicians. It was a standard practice to use the pros when recording. Jim

had recently finished recording sessions with Dino Valente in a rock and

roll format and decided to record David in a like manner.r>

Unfortunately, the tapes embarrassed David because folk music was the

genre of the moment. Dickson wasn't able to secure a recording deal for

David, so he suggested he should switch from lead singer to a harmony

singer. David had been in Lex Baxter's Balladeers and resisted the

direction. In the meantime, David kept a suitcase in Dickson's garage and

slept on different people's couches.

One day David arrived at the

World Pacific studios high with excitement. He had found two guys he

wanted to sing harmony with and if Dickson would get involved he was sure

they would let him.

Dickson was familiar with Jim McGuinn, but had

never heard of Gene Clark. David told Dickson he would only be a singer

because both of the guys were much better guitar players than he was.

David's method of guitar playing was of the school of Travis Emundson -

just learn the chords when you need them for the song you want to sing.

It was late at night, when David brought Jim and Gene to the World

Pacific studio. Dickson asked them to sing a few songs. He felt their

vocal sound was worth his time, since vocal blend was the most difficult

achievement for a group. Their pseudo English accents did cause him to

wonder about their motivation

.

Jim and David begged Dickson to go

with them to a movie they had seen, "A Hard Days Night." He finally

understood the accents. The lads were excited about the movie.

On

the sidewalk outside the theater, while McGuinn was busy explaining to

Dickson his realization that most of the Beatles' songs were based on folk

chords, David was swinging around a lamp pole like Gene Kelly and yelling,

"I want to be a Beatle!" McGuinn was also excited about George Harrison's

guitar. When he first heard the sound, he was sure it was a 12-string

guitar, but in the movie it only looked like a 6-string from the front.

Then, George turned sideways and Jim could see it was a Rickenbacker

electric 12-string guitar! This veteran 12-string player had to have one

of those magical instruments at any cost.

A few days later, David

and Roger were standing on Hollywood Boulevard talking about how to become

a band like the Beatles. David felt he could play bass, but they needed to

find a drummer. They felt it was important for everyone to look English.

As they were talking, a guy came strutting down the street who looked just

like two of the Rolling Stones rolled into one package. They both pointed

and said "him!"

It was an 18-year-old who was calling himself

Michael Clarke. Roger had seen him in San Francisco playing bongos and

they asked Michael if he could play drums. "Sure," he half-heartedly

answered. They took him to the studio, configured some cardboard boxes as

drums and set a tambourine up for the snare drum. Michael sat down with a

pair of sticks and began practicing.

David quickly realized he

couldn't concentrate on harmony while playing the bass. He asked Dickson

to get another player. Dickson had recorded with an accomplished mandolin

player named Chris Hillman. He first encountered Chris with the Bluegrass

group, Scottsville Squirrel Barkers, then the Golden State Boys with Vern

Gosdin. Their latest Dickson recording at World Pacific was the album,

which became "The Hillmen" featuring Vern and Rex Gosdin, Don Parmley, and

Chris.

Dickson felt Chris's musicianship and the way he supported

vocals would make him a good candidate to learn to play the bass, so he

invited Chris to a rehearsal.

Dickson wasn't planning on recording

with the bass and drums, but did want them for live performances. He

formed a business partnership with the original three musicians. He

quickly realized in order for the partnership to survive, he would have to

feed the lads who had no money or jobs. "Guess I have to feed you now,"

was the line Dickson used when he felt the late night session was over.

Hamburgers were the reward for a good night's work.

The group was

making progress. Dickson used his own money to bring in some studio

musicians to play on two songs: "Please let Me Love You" and "Don't Be

Long." He sold the songs to Elektra Records and told Jack Holzman to

choose a name, but don't identify the members. He chose the name

"Beefeaters." Maybe it was the "British Invasion" or a gin bottle on the

desk inspiring the moniker.

The group"s ability to perform live was

still in question. They booked a show at the Troubadour. David played

without an instrument and the result was an awkward singer slinking around

the stage in the style of a chubby Mick Jagger. The audience was not

impressed. David quickly grasped he wasn't going to be the next rock

screamer and he needed the protection of a guitar. He joined McGuinn in

lamenting about Gene's tempo changes. Gene felt songs were more dramatic

if they were sung in a slower tempo. This habit drove the perfectionist

musician, McGuinn, to distraction. Bobby Darin had impress upon Jim the

importance of timing and to hear a song drag out of tempo was tough for

him. The timing issue was the point David chose as a tool to undermine

Gene's confidence as a guitar player. David had to quickly learn all the

chords to the songs and Gene grabbed a tambourine as a prop. It was the

beginning of the major rifts which often plagued the band: personalities,

perfection and politics.

By then Dickson felt there was a future

for the group and brought Eddie Tickner into the partnership to handle the

business end. They needed money for instruments and the lads wanted to

have suits like the Beatles. Eddie found a very wise investor with an

available $5000 whose heirs still collect 5% of the initial royalties to

this day.

Dickson drove McGuinn, Clarke and Crosby to the music

store. Jim carried his Pete Seeger model 5-string banjo and Gibson

acoustic 12-string guitar, a gift from Bobby Darin. He wanted a

Rickenbacker 12-string and was willing to trade in both of his instruments

to get one.

After the instrument purchases, Dickson dropped Jim off

at the Padre hotel. Mae Axton had come to town, so Bob Hippard found Jim a

room at the Padre Hotel for $4.00 a night. The moonbeams danced around the

room as Jim played the guitar until he fell asleep, propped up against the

pillow of the bed holding his new prize possession.

To be

continued...someday.

|